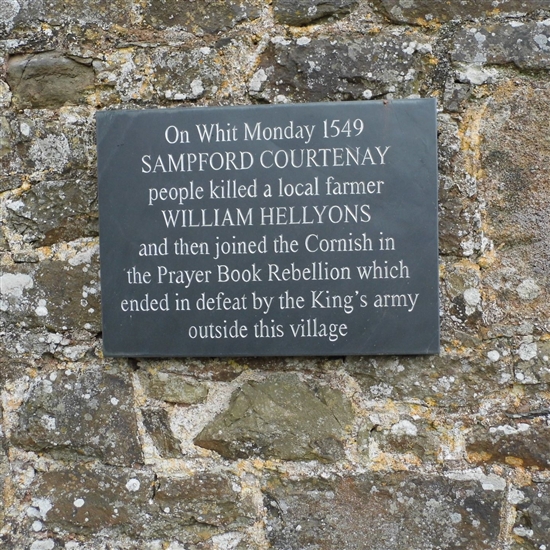

Battle of Sampford Courtenay

Battle of Sampford Courtenay

18th August 1549

Name: Battle of Sampford Courtenay

Date: 18th August 1549

War Period: Early Modern

Start Time and Duration: Unknown (estimated to be afternoon until evening).

Outcome: Loyalist victory

Armies and Losses: Army of John Russell claimed to be 5000-8000 strong versus around 2000 insurgents. Russell’s account of the battle estimates the rebels suffered over 1200 casualties for the loss of only 10-12 of his troops, although a larger number were reportedly wounded.

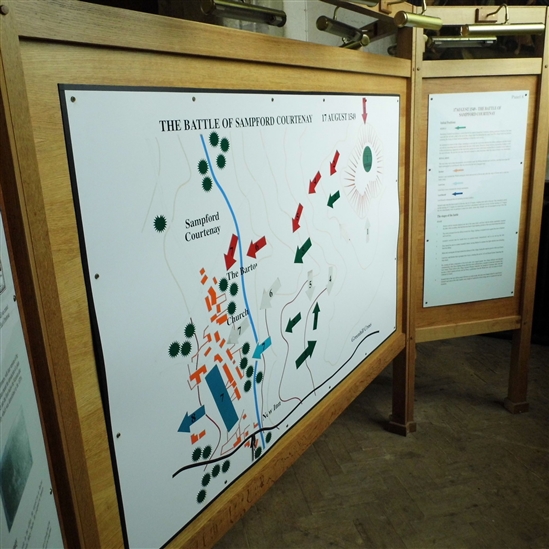

Location: At the modern-day settlement of Sampford Courtenay, with a rebel encampment in the hills along the parish boundary with North Tawton, and an unconfirmed ambush site lying between the two locations.

Loyalist forces overrun a fortified rebel encampment, despite ambushes in the surrounding fields, before routing the insurgents from their final stronghold of Sampford Courtenay.

Two weeks after breaking the siege of Exeter, the Crown forces of Lord Russell moved to crush the Western Rebels, who had regrouped 20 miles west, at their original headquarters at Sampford Courtenay. The loyalist army was significantly enlarged by further reinforcements, including a thousand Welsh militiamen and retainers led by Sir William Herbert and renewed support drawn from the surrounding area, and so may have outnumbered the insurgents by as many as four to one. Additionally, Russell’s command comprised a combined arms force, including experienced retinue members and foreign mercenaries, whereas the insurgents had only infantry drawn from the same pool as the shire militia supported by artillery. This disparity in numbers, equipment, and experience gave the resultant action the character of a last stand by those too ideologically committed or compromised to disassociate themselves from the revolt, with the odds heavily stacked in the loyalists’ favour.

After marching the 7 miles from Exeter to Crediton on 16 August, Russell approached North Tawton on the 17th, where one of the rebel commanders, Maunder, was reportedly captured in a skirmish between opposing scouting parties. The following day, the loyalists commenced their attack on the insurgents, who had dispersed their forces between the village of Sampford Courtenay itself, a fortified hilltop camp to the north east, and an ambush party concealed amidst the fields in between. Despite the insurgents’ skillful deployment, which made effective use of their comparatively small force, the numerical disparity with Russell’s far larger army meant that the battle was a relatively brief affair.

Upon arriving from North Tawton, the loyalist forward battle, led by Lord William Grey and Sir William Herbert, deployed from the march to assault the rebel camp, using pioneers to breach the thick enclosure hedgerows while their artillery exchanged fire with the insurgents’ gunners. The loyalists’ advance was, however, disrupted by an ambush from Humphrey Arundell’s rebel contingent, which tied down a significant portion of Grey’s troops and prevented them making further headway. While Arundell’s ambush devolved into a standoff amidst the enclosures, with both sides exchanging artillery fire for an hour, Herbert managed to press onwards and overrun the rebels’ fortified camp, killing several hundred insurgents including Underhill, another of their leaders.

With the loss of their camp, Arundell and his followers fell back into Sampford Courtenay, but swiftly abandoned their positions and fled as the remainder of the loyalist force arrived onto the battlefield and prepared to encircle the village. Inevitably, without a cavalry arm to cover their withdrawal, the insurgents suffered heavy losses, with Russell’s report of the action claiming that around 700 were slain before nightfall curtailed the pursuit. Loyalist casualties were limited, in part due to the rebels’ archery struggling to inflict lethal wounds on armoured soldiers, and in part due to the overwhelming advantage in numbers enjoyed by Russell’s forces. Accounts of the battle mention that a Welsh gentleman, Ap Owen, presumably a part of Herbert’s contingent, was killed in an attack on the fortified edge of Sampford Courtenay, perhaps as a consequence of an overenthusiastic pursuit or indicative of a small delaying action fought during the rebel retreat.

Even with the rebels vanquished, Russell and his forces were uncertain of victory after repeated previous ambushes and counterattacks, and remained in a state of readiness throughout the night until it became apparent that the insurgents had abandoned the field. The capture of Arundell and the rebellion’s ringleaders at Launceston the following day cemented the insurgency’s military defeat and paved the way for a series of reprisals as suspected rebel supporters were hunted down and executed by Anthony Kingston over the summer months.

The location of Sampford Courtenay remains unchanged, securely anchoring at least part of the battle within the modern landscape, while the rebels’ hilltop camp was likely to have been situated on the large hill north of Greenhill Cross, to the northeast of the village. This positioning would accord with the loyalists’ probable line of advance, along the modern A3124 from North Tawton, which would place the rebel camp to their northwest as they approached the village from the east. While there are no clear indications of where Arundell’s ambush occurred, the fact that it was sprung as loyalists assaulted the rebels’ camp, and that the insurgents subsequently retreated into Sampford Courtenay, indicates that the network of fields between these two locations may be a viable site. Given that much of the fighting occurred in and around the rebels’ camp, which remains undeveloped arable agricultural land, there is the potential for archaeological survival of battlefield debris, particularly those connected with the exchanges of artillery fire during the assault on the hilltop and during Arundell’s ambush of Grey’s forces. Evidence of the earthworks of the rebel camp may also survive below ground. The site is open and accessible via surrounding roads leading to Sampford Courtenay village.

An assessment of the Prayerbook Rebellion battlefields undertaken by Dr Glenn Foard and Alex Hodgkins on behalf of Devon County Council in 2009 is available from Archaeological Data Services at https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/issue.xhtml?recordId=1208573.

This entry has been provided by Alex Hodgkins.