The Battlefield

The location of the battle close to Mortimer’s Cross is established from the naming of the battle. However the exact location of the action is far less easily determined. There are two alternative sites for the battle, one at or immediately south of Mortimer’s Cross itself, the other 1 mile to the south east of Mortimer’s Cross, immediately north west of Kingsland, where the monument was erected in 1799.

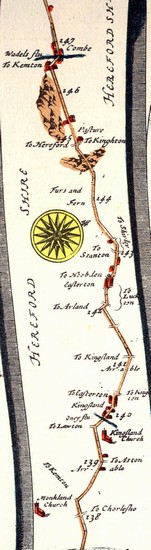

The potential battlefield area extends across three townships: Kingsland, Aymestry and Shobdon. There appears to be a distinction between the land on the valley floor of the Lugg and the higher ground. The flat ground between Mortimer’s Cross and Kingsland would appear, from field name evidence to previously have been under open field cultivation. This included Kingsland Field and Great West Field. Ogilby’s Itinerary shows that part of the area between the Roman road and Kingsland remained as open field arable as late as 1675. Although the 1940s aerial photographic sources do not reveal any evidence of ridge and furrow, the pattern of fields on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey six inch mapping of the 1880s does seem to reflect the layout of hte earlier furlongs and strips.

In this area on the valley floor today there are regular fields and straight hedges, but on the rising ground the 19th century maps reveal what appears to be a more anciently enclosed landscape of irregular fields and winding sometimes hollowed and embanked lanes. Also on the higher ground there areas of woodland of varying sizes, present on the early 19th century Ordnance Surveyors Drawings and probably reflecting a medieval pattern of woodland, for in 1086 the manor of Shobden had extensive woodland. On the valley floor to the west was an extensive area of wetland called Shobden Marsh, identified as marsh on the Ordnance Surveyors drawings, with an extent clearly defined by an areas of peat deposits on the British Geological Survey mapping. This would have made the valley floor between the higher ground of Shobden and the Pinsley Brook largely impassable. In contrast the valley floor of the river Lugg seems likely to have been fairly well drained and cultivated in the medieval period. Only in a very narrow strip alongside the river, where in places the river has been somewhat straightened from its earlier course, clearly visible on the aerial photographs as a series of abandoned meanders, is there any wetter ground. Wig marsh as shown by Howard and by Haigh on the eastern side of the battlefield represents a misunderstanding of Gregory’s Chronicle because, as Hodges has shown, that refers to Wigmarsh or Wydmarsh on the edge of Hereford.

The pattern of settlement in the 1820s was one primarily of dispersed settlement, probably reflecting a medieval pattern of dispersed farms and hamlets, but there do appear to be a number of nucleated settlements with open fields, of which Kingsland is the most significant in relation to the battlefield. While Kingsland seems likely to have been a nucleated medieval settlement, Mortimer’s Cross was just a small cluster of houses at the crossroads in 1820 and may have had no occupation in the 15th century, as other nearby cross sites, such as Legion Cross and Stockley Cross have remained.

The road pattern was transformed with the construction of turnpikes in the 18th century, diverting the routes through Mortimer’s Cross and giving increased importance to what was probably an existing route across the Lugg at Mortimers Cross. The present stone bridge over the Lugg was constructed in 1771 and widened in 1938, according to the inscription on the bridge. However, while the present structure may be a result of the creation of the turnpike road, which altered the priorities of the roads, the route seems likely to have already been in existence much earlier, for the the road network and footpath network, a good indicator in this landscape of the earlier road network, converges on the bridge. Moreover, in 1675 Ogilby shows two route running in the direction of Mortimer’s Cross from the post road, where it passes through Easthampton, to the village of Lucton, which lies on the east side of the Lugg. While the Roman road remains as a minor road today, the London - Aberystwyth road mapped by Ogilby in 1675, which survived as a lane in 1820 over part of the route, has now been completely lost where crossing the battlefield, except for a public footpath. Before the construction of the turnpike roads in the 18th century, the major road from Wales was very different. Recorded in 1675, it ran through Kingsland, just over a mile to the south east of Mortimer’s Cross.

It seems clear that the dispute over the location of the battlefield and the nature of the action will only be resolved, if at all, by the detailed reconstruction of the historic terrain, including the road network as it was in the mid 15th century, and by an intensive and systematic archaeological investigation to locate evidence of the action.