Preston Campaign 1648

April-August 1648

In May 1646, with his last field army defeated at Stow-on-the-Wold two months earlier, King Charles I surrendered at Newark to the Scottish army which was fighting with Parliament. The Scots had been in alliance against the king from late 1643 under the terms of the ‘Solemn League and Covenant’. However, this agreement had weakened and the Scots were prepared to come to terms with the King, in return for the introduction of the Presbyterian religion into England and the exclusion of royalists from public office. But the King was not prepared to accept these arrangements. At the same time, the Scots were negotiating a financial settlement with their allies for their past participation in the war. After part receipt of a £400,000 payment, the Scots washed their hands of the King and handed him over to Parliament in February 1647, which subsequently moved the King to Holdenby House in Northamptonshire.

During 1647, the majority ‘Presbyterian’ faction within Parliament wanted to come to moderate terms with the King and disband the army. The army, more radical, were concerned about an accommodation with Charles, which could deny it arrears of pay and undo much of what it had fought for. In June 1647, the King was seized from Holdenby by a faction in the army and moved to Hampton Court. New peace terms, still relatively moderate, were put to the King by the Army Council under the title of the ‘Heads of the Proposals’. Charles dismissed these, possibly hoping that he could make political capital out of the dissension between the parliamentary Presbyterians, the City of London and its militia on one side and the army, with its high proportion of religious independents, on the other. Poor advice from his aide Ashburnham and a belief that the army was beholden to him also led Charles toward this decision.

In late July 1647 a London mob attacked Parliament, ostensibly over control of the City’s militia committee, but with frustration over the failure to restore the King’s rights and privileges as an underlying factor. This was exploited, if not instigated, by the City authorities, along with some Presbyterian members of Parliament and developed quickly into the City militia being used to defend what had become a counter-revolution against the army and its friends in Parliament. In response, Sir Thomas Fairfax moved the New Model Army into London in early August to remove the challenge to Parliament's and the army’s authority.

Whilst severe disagreements over what former parliamentarian allies judged as an acceptable constitutional settlement were all too apparent in the events of July and August 1647, views within the army also varied widely. In late October and early November 1647, the army commanders and representatives of the soldiery debated the settlement issue at Putney. However, the demands of the ‘levelling’ faction within the army were unacceptable to the Army Council and its ‘ring-leaders’ were arrested at a muster of the army at Ware in November 1647. Against this background of dispute amongst his old enemies, Charles had been in secret negotiation with the Scots. This resulted in an ‘engagement’ in late December 1647 between Charles and the Scottish Lords Hamilton, Lanark, Lauderdale and Loudon to introduce the Presbyterian Church in England and for one of Charles’ sons to be resident in Scotland, in return for Scottish help in regaining his power.

Unrest was not just limited to London. In Wales Major General Laugharne and Colonels Powell and Poyer were in dispute with Parliament over arrears of pay and when efforts to disband their forces were made, they mutinied in February 1648. Although Laugharne was defeated by forces loyal to Parliament at St Fagans in May, it was not until the mid July that the south Wales revolt ended with the capture of Pembroke castle. Nevertheless rebels in Anglesey held out until October.

In Kent the Mayor of Canterbury’s attempts to force the shops to open at Christmas 1647 resulted in serious unrest which was only quelled when a New Model Army regiment was despatched to the county in January 1648. Those accused as ringleaders were tried in May but were acquitted. The refusal of the judges to confirm this until Parliament had responded resulted in a petition from the Kent gentry calling for the King’s rights to be settled. Open revolt occurred when the County Committee declared the petition seditious and sent troops to repress it. Only the intervention of regiments from the New Model Army under Sir Thomas Fairfax brought events under control with Fairfax defeating the rebels at Maidstone overnight on 31 May/1 June. The remnants of the rebels escaped north into Essex, which was also in revolt, and royalists in the county were eventually cornered in Colchester and forced to surrender after a bitter siege on 28 August 1648.

In northern England, English royalists captured Berwick and Carlisle in late April 1648 in preparation for the invasion of the Scottish Engager army under the Duke of Hamilton. But political divisions north of the border and the slow mustering of the army meant it did not cross the border until early July. Delayed by the manoeuvring and skirmishing of Parliament’s Northern Association army under Major General John Lambert it was not until 9 August that the Engagers reached Hornby in Lancashire. It was here that a final decision was taken to use the western route via Preston southward into England rather than through Yorkshire, probably in the hope that the rebels in north Wales could lend the Engagers their support.

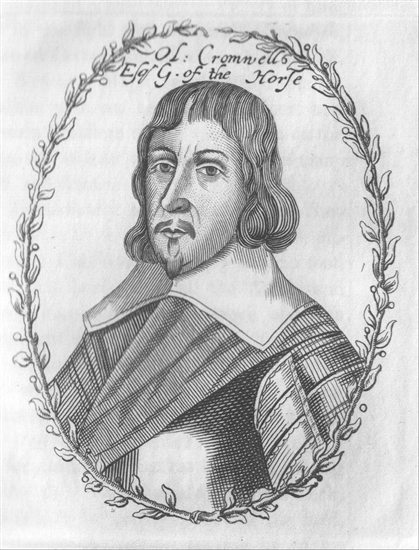

Lieutenant General Oliver Cromwell had been engaged in operations in south Wales until mid-July with elements of the New Model. The week after the fall of Pembroke he marched his small army to Leicester, placing him in the middle of the country ready to respond to the Scottish advance on either the west or east side of the country. By 12 August he had rendezvoused with Lambert between Knareborough and Wetherby.

At Hornby the northern royalist forces under Sir Marmaduke Langdale were detached from the army and marched eastwards toward Settle to provide a flank guard to the main force which was to advance to Preston and cross the river Ribble. John Middleton, a Scottish officer who had been in Parliament’s service during the first Civil War, led the cavalry vanguard of the main force followed by Lieutenant General William Baillie with the foot. At a distance behind came Major General George Munro with a ‘New Scots’ contingent of cavalry and infantry that had been serving in Ireland since 1642.

Cromwell was determined to attack the Engager army and advanced to Skipton and then to Gisburn on 15 August , only ten miles from Clitheroe, which Langdale had reached on 13 August. Langdale reported the close proximity of parliamentarian forces to Hamilton on 15 and 16 August, but these warnings were ignored and overnight 16/17 August Cromwell’s men moved to attack Langdale’s forces around Longridge.

Over the course of the morning Cromwell’s men forced the northern royalists back toward Preston as Langdale sent increasingly urgent messages to Hamilton. Whilst limited reinforcements were provided they were not enough to stem the flow and the parliamentarian forces caught the Scottish infantry as they were attempting to cross the Ribble. Middleton’s cavalry had already crossed and Munro’s force was too far behind to offer assistance. The Engager army was defeated, though a sizeable force of infantry and cavalry were on the south side of the Ribble. These forces continued their march south via Wigan until they made a stand at Winwick, just north of Warrington. Here a further action was fought with the New Model and Northern Association forces eventually overcoming stubborn Scottish resistance. Many of the Scots were killed or captured though some escaped to Warrington where they surrendered with the contingent that had been posted there. The remnants of the Scottish cavalry surrendered at Uttoxeter on 25 August.

Following the defeat of the Scots the position of rebels elsewhere in the country became untenable. The siege of Colchester ended on 28 August, leaving only Pontefract Castle in royalist hands which eventually capitulated in March 1649 . Charles I’s scheming with the Scots and the failure of the subsequent invasion helped lead directly to his trial and execution in January 1649.