The Archaeology of the Battle

A number of archaeological finds have been made on the battlefield, but all appear to have been chance discoveries. No record has yet been identified to suggest that there has been any more recent metal detecting or other archaeological investigation of the site.

Silver coin of King Stephen of 1137 was found in a field adjoining Standard Hill grounds in about 1851. A similar coin had also been found nearby in 1839 and close to it the silver hilt of a sword. In about 1894-5 ‘on the Standard Hill itself a beautiful little bronze cross, about four inches in length and ornamented on its face with a knot decoration, was discovered.’ This was believed to have been taken to Edinburgh for identification. Finds continued to be made in the 20th century because Burne mentions ‘relics’ having been occasionally ploughed up, referring to the then (1952) owner’s father who is said to have discovered ‘relics’, items which might have been donated to York museum.

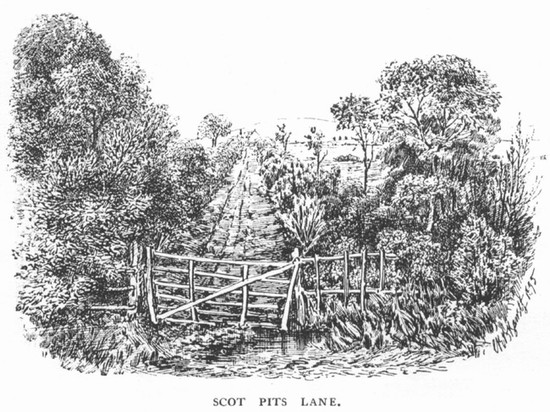

The most significant discovery is the evidence of burials, apparently of both horses and men, found in the 19th century found in the vicinity of the Scot Pits, the fields immediately to the north of Scot Pits Lane.

This location has long been known as the site of mass graves. In the later 17th century Dugdale reported ‘the Ground whereon it was fought, lying about two miles distant from North Alverton (on the right hand the Road, leading thence towards Durham) is to this day called Standard Hill, having in it divers hollow places still known by the name of the Scots Pits.' In the mid 18th century Roger Gale reported a few trenches still to be seen in his day called The Scots Pits, said by tradition to be the burial pits of the slain. However early in the 19th century ploughing apparently destroyed all the earthwork evidence. However Leadman in 1891 reports that within living memory at Scotpits Lane "bones of men and horses have been found…’. It is uncertain whether Barrett’s comments are at least in part independent from Leadman and others, but of Scot Pits Lane he records that ‘hedgers and ditchers have frequently found fragments of weapons and bones there.’

In any future archaeological study of the area for earthwork or crop and soilmark evidence it will be necessary to take account of the presence of a Brick Kiln Field in close proximity to the eastern end of Scotpit Lane which may have generated quarry pits in the area which might need to be identified to avoid confusion with mass graves.

The presence of these burials behind the traditional location of the English lines has caused considerable problems for most earlier authors. The re-interpretation presented here resolves this difficulty, placing the mass graves in the centre of the action.

The most bizarre interpretation was that by Barrett, who reversed the location of Scots and English deployments, something that Burne has pointed out is impossible. Others have attempted to explain the location of the graves by attributing them to the small numbers killed Prince Henry’s cavalry charge through the English lines and his attack on the cavalry and horses in the rear of the English battalia. Indeed, in an uncharacteristic lapse of judgement, even Burne specifically avoids his normal interpretation regarding the significance of mass graves: ‘I usually attach great significance to the position of the battle grave-pits, as probably indicating the approximate centre of the battle, but this must not be taken as an absolute rule, especially where it conflicts with other evidence.’ However the new evidence discussed above would appear to resolve this problem and associate the Scot Pits directly with the dead from the main Scottish attack.

Though it is perhaps most likely that the tradition is a later rationalisation of an existing name, in the 19th century Red Hill was reported as traditionally associated with the battle, the Red name supposedly relating to the hillside streaming with blood. Though perhaps spurious, it is interesting to note that the location lies even further south east than Scot Pits.